I. Introduction

Computer, generate a book that will teach me how to maximize my chances of winning tournaments for the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game. The contents must be written by one of the most prolific players of all time. Disable safety protocols.

Road of The King by Patrick Hoban is a fascinating read that promises to improve your performance in competitive games but at the risk of becoming a villain in the process.

II. Background Information

Trading Card Games are a subset of card-based tabletop games which are in no small part defined by unequal access to those cards. Cards are usually acquired through randomized booster packs, preconstructed decks, and promotional events. Players are encouraged to buy more product and trade with each other in order to build out their collections of available cards. This uneven access to resources means players are expected to build a custom deck using their limited available cardpool prior to sitting down at a table. This is the world of hidden information games in which your opponent could, in principle, be using virtually any combination of thousands of cards.

Before we talk about the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game in particular, we must first talk about the progenitor of all TCGs, Magic The Gathering. Mark Rosewater, its lead designer, outlines his design process as a balancing act between primary player personas; Timmy, Johnny and Spike. These three personas form the backbone of nearly all aspects of the game’s design, but more importantly, they illustrate the primary relationships players have with the game as a whole. These personas are so fundamental that their usefulness transcends MTG specifically and can be applied to nearly any customizable competitive experience.

But who are Timmy, Johnny and Spike? What motivates them? Why do they play the game?

Timmy is the power gamer. He wants to win in an impressive way with powerful cards and dramatic plays. Timmy won’t be satisfied with a win he considers lame. He is often characterized by a friendly attitude.

Johnny is the combo player. He wants to express his creativity through innovative strategies and unique interactions. Johnny won’t be satisfied unless his creative idea pays off, but doesn’t mind taking losses along the way.

Spike is the tournament player. He wants to win. He won’t be satisfied with a loss. He can be ruthless in this pursuit.

The vast majority of players embody aspects of each persona, perhaps leaning harder into one or two. For an illustration of this idea, I think of myself as a Johnny/Spike. I gravitate towards interesting or unique deck types or interactions and then try to optimize them for success. A friend of mine is a Timmy/Spike. He wants to win big with aggressive, powerful strategies operating at the optimal balance of strength and efficiency. The both of us enjoy friendly banter and rapport building during a game that would make Timmy proud.

We strive to increase the probability of a win to its absolute limit, but to do so in such a way that we maximize the fun had along the way. However, certain strategies are forever blocked off from us because of this. I won’t use something straightforward or overused. He won’t use something slow or defensive. We are forever handicapped by an unwillingness to choose victory over all else. Likewise, the friendly decorum of the Timmy closes off dark arts that would otherwise prove helpful for securing certain advantages during play.

III. Getting To Know Our Hero

Patrick Hoban is one of the most prolific players in the history of the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game. Playing the game competitively since 2010, he made a name for himself with consistent top tournament level performance, surpassing the previous record holder of greatest number of tournament top placements to date..

The foreword of the book serves to paint a picture of what kind of person Patrick Hoban is, and right out of the gate things start to look eerily familiar. His close friend and teammate describes Hoban’s mental habits and personality using an anecdote involving a discussion of human immortality and cryonics. He is a Devil’s Advocate who defies commonly accepted paradigms and strives to overcome his biases in pursuit of the right answer.

“Pat’s optimism for solving the impossible is largely responsible for his proven record of stealing tournaments with novel card interactions, time and again. His intuitive eye for abstract relationships and his willingness to attempt strategies rejected by the hive mind are what has made him the most successful player to ever touch the game, and it is why he will persist as a dominant threat in any arena he competes in. He does not see the accepted standard as correct. Pat’s mind dwells not on the way things are, but on the way things could be.”

One of his most notable contributions to the game was popularizing the use of Upstart Goblin at three copies, the maximum allowed. The card is very simple. You draw 1 card and your opponent gains 1000 life points. This functionally reduces the player’s deck size from 40 cards to 37, increasing consistency for effectively no cost (as life points are essentially meaningless unless they hit zero and end the game). His whirlwind series of victories using this approach popularized the deck compression strategy and the card was jokingly referred to as “Upstart Hoban” for years.

“We got to the top because we played more, we cared more, and we were more driven. We had encountered more scenarios, had a better understanding of the relationships, and had better shortcuts. Can you enter a 1,000-person tournament honestly believing you’ve practiced more than every single other guy in the room? I could with almost every tournament I entered.”

Patrick Hoban is the rare breed of pure Spike. His advice can be ruthless and his single minded pursuit of victory is unwavering. What is his preferred playstyle? If he has one, it’s completely independent from the deck he’s currently playing. He will use the deck he believes will bring him victory. Everything he says, does and advocates for is instrumental to a singular goal – maximize the chance of winning tournaments.

Very few players before him had taken such an analytical approach to deck building theory. Everything in this book is designed to leverage his systematized knowledge and claw the chance of success as close as possible to 100%. As a friend of mine put it, “He wants to ‘Moneyball’ Yu-Gi-Oh!”

IV. Laying The Foundation

“Much of this section will focus on what it means to be rational.”

Hoban sets out to explain to his audience how he thinks about anything at all before he goes into how he thinks about games in particular. Drawing on concepts and lessons learned from economics, cognitive psychology and entrepreneurship, he presents a toolbox about how to think clearly, avoid mistakes, and win. It’s one man’s screed about cognition frontloaded in the attempt to discuss his goal of choice with a like-minded audience. If this sounds familiar, it should.

“People don’t intentionally make bad choices or choose to make themselves worse off than they were before, but the way we perceive the world, and how the world actually is, are two separate entities.”

The section outlining biases alone contains 41 different biases and errors of thought to avoid. The reader is guided through a rationality mini crash course, complete with thought experiments, anecdotes, cited studies, and quotes by experts. Specific mental techniques are outlined and Hoban expects the reader to walk away from this section ready to apply these lessons to all domains of their life.

V. Hiring For Your Startup

“As we continue, we’ll find incredible similarities between things such as the correct way to prepare for tournaments and seemingly unrelated things like the correct way to run a business, because the process of making good decisions looks very similar across all the different disciplines.”

Some goals are more easily accomplished with a team, which Hoban refers to as a circle, but the ideas discussed feel quite a lot like hiring for a startup. He describes building a highly specialized circle of competence containing specialized roles. The roles support each other so that any given member has a much higher chance of winning the tournaments they attend. He recommends having as few people as possible, each filling a specific specialized niche. He warns against inviting in someone merely because they are your friend. Your circle is your startup and everything you do is your proprietary company secret. Hoban takes this idea very seriously and warns against inviting in anyone who could jeopardize the circle’s mission.

Those untrustworthy might undermine you.

“The overarching problem with crafting an effective circle is that we are forced to make decisions with limited information. Potential candidates have asymmetric information that they can leverage to strategically manipulate our trust. When someone tells us that they’re trustworthy or that they’ll work hard, we only have an idea of whether or not those things are true.”

Your friends might not be good enough.

“There were others with whom I didn’t feel like I gained much by working alongside, or that they were unmotivated and didn’t put in as much effort as the rest of us did. Make sure that the people you choose to work with have the same motivations that you do.”

Outside agents might try to trick you into revealing something valuable.

“If we have a circle that’s desirable, those not in it have an incentive to strategically misrepresent their intentions to get information from us. We’ve seen great, potentially event-winning, ideas go down the drain when they were leaked before the event started.”

It should come as no surprise that Patrick Hoban leveraged these lessons years later to found his own startup, Parvenu, named in honor of the French word for upstart.

VI. Technical Play

“Good technical play is about a fundamental understanding of the basics”

Summarizing and evaluating Hoban’s breakdown of the fundamental skills of TCG play is beyond the scope of this review. I’m pushing the bounds of common sense already by submitting this to the book review contest. If you are a reader of the blog and also play TCGs this section will be extremely valuable. New players will gain a newfound appreciation for the depths of strategy in high level play, and seasoned players can benefit from seeing their already internalized lessons spelled out and systematized.

VII. Getting To Know Our Competition

The game begins before you place your deck on the table. Just as you must understand all the meta-relevant cards you could face, you must understand all the types of players you could face. Accurately gauging the skill level of your opponent will tell you what level to play at. Each skill level demands a gradually increasing level of nuance and strategy needed to manipulate and defeat them. Afterall, there’s no point making a fancy bluff that requires deep game knowledge if your opponent barely knows what the cards do.

This is where the book really shifts from looking inward to improve yourself to looking out at your opponents.

The Below Average player is described as irrational and overconfident. They will play aggressively and use cards and effects as soon as they can legally activate them. They will not make predictions or pick up on any false reads you send. Their knowledge of the fundamentals will be poor and they will not seek to improve nor attend tournaments regularly. They will have a hatred of current top-tier decks and erroneously take pride in not using them. They will be emotionally attached to their deck of choice which will be chosen based on emotion rather than ability to win.

“They frequently have a hatred of the meta decks and believe that their refusal to play them somehow makes them superior, as if playing Ice Barriers were somehow “creative,” despite the fact that the cards basically come as a pre-packaged deck in a single pack, and even all share the same name so that one could not possibly fail to realize that they are supposed to go together”

“They see their deck as a part of their “person,” and are emotionally attached to cards and deck types. They will make deck decisions based on how much they like an arbitrary aspect of their cards, such as the artwork.”

Hoban denigrates this player type, but does not really pay them much mind beyond easy wins at the beginning of tournaments. You won’t see them once your record racks up a win or two and you just have to avoid a fancy bluff that will fail to bait them due to their own ignorance.

Merely Average Players are also characterized as “non-thinking” players with a poor grasp of theory and technical play. These players are by definition the most common and it’s recommended to playtest the most against opponents of roughly this caliber due to the high likelihood of playing against them.

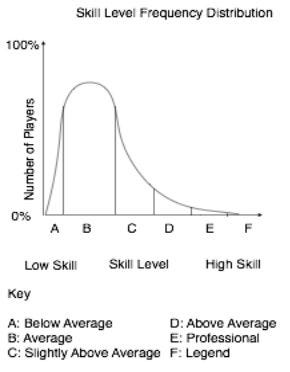

The classifications then tick steadily upward to better and better opponents with a corresponding decrease in prevalence and increase in skill, knowledge, and the ability to make reads. This reaches its peak at “Legend,” or players so good that they’ve made a name for themselves and have a tangible record of tournament results to back up their notoriety. These players make decisions that ultimately shape the format and have a mastery of technical play and metagame knowledge. Hoban’s description of these players, whom he counts himself among, is telling.

“They are well-versed in all areas of the game. They are master manipulators and persuasive geniuses.”

If you are currently up in arms about how reductionist this classification system can be, don’t worry; Hoban’s model of the playerbase does include room for exceptions. He carves out a space for “one-hit wonders” who do well once and are never seen again, as well as “slightly above average players who have a strong attachment to a non-meta deck, similar to below average players.” In Hoban’s world, good players play good decks often enough that the alternative is really not worth considering. At the major tournament level he is broadly correct. On average, skilled players who have bothered to travel to major tournaments will be using strong decks. You might be crying out that this isn’t always the case, and you would be right, but he acknowledges these players as exceptions not worth preparing for.

“Tournaments aren’t won by preparing for every single possibility. They’re won by preparing for what will happen on average. Preparing for every exception is simply not worth it.”

He includes the following chart as a semi-helpful visual aid.1

VIII. The Mental Game

“We’re engaging in a battle of the minds with the opponent. This is competition in its purest form. There are no bad draws, no lucky top decks, and no brick hands when it comes to a battle of the minds. Those exist only in the realm of the deck. The mental game is a true test of one’s ability, for it eliminates these factors entirely. This is a battle of intellect, wit, and cunning between two players. The mental aspect embodies the very essence of competition. It is a show of dominance as an art form.”

This section of the book is where Hoban truly starts to show how orthogonal the values of a Spike can be from the values of a Timmy or Johnny.

The Mental Game contains all meta level knowledge and strategy that you can utilize to secure your position. This section is about leveraging all the little signals your opponent gives off that leak information. In a game of hidden information, the players are the biggest security flaw and there’s nothing in the rules preventing you from abusing that fact. This is a mental battle of information theory, bluffs and double bluffs, and subtle manipulations.

As noted earlier, the very first step is to gauge your opponent’s skill level, and in so doing, learn which level of play will put you one level above them. It does no good if you bluff an opponent who won’t read into your subtle hint. Likewise, it does no good if your opponent sees right through your bluff and at the truth beneath.

Going a step beyond, Hoban encourages learning the current tournament scene. If skilled players consistently top events, then studying the results of recent tournaments can give you immediate material information. If you don’t recognize the name sitting across from you, then their probability of being merely an average player increases.

But what to do once you have ruled out your opponent as a known quantity on the competitive dueling circuit? If you guessed it’s to observe how your opponent plays to get an understanding of their skill, then you have gotten way ahead of yourself!

The true second step is to profile your opponent based on their gear. Many players will show off prizes they won from performing well at a major event including playmats and card sleeves. This can be contrasted to using the paper playmats that come with starter decks, a mark of a truly new player. Some players have been known to intentionally misrepresent their own level of skill and seriousness by using low quality items, but such a thing is uncommon enough to ignore.

“We should use our common sense to gauge where on this spectrum our opponent falls. It gives off free information, and there’s no reason to not use it.”

And the next step in this battle of wits? It’s time for our first confrontation with the enemy forces. Our mental skirmish begins. We will now perform a phishing attack.

“The number one way to figure out what our opponent knows is to ask. People love to talk about themselves. The more they say, the more information they give. People don’t tend to lie when asked questions like “Hey, where are you from?” Anything they respond with is probably true and can be used to help us gauge our opponent.”

Now we truly begin to read the opponent. Everything they do, everything they say, every little detail is a signal that can be read to our own advantage.

“We can learn to pick up on the signals our opponent is sending us by asking the following: What are they doing? Why are they doing it? Why have they chosen to do it now, as opposed to some other time? And finally, what that might imply that they have?”

“Most opponents, even above average opponents, typically won’t try to conceal what they’re thinking about. If they’re asking us a question or thinking about something, we should be asking ourselves why they might be asking that question and why they’re asking it now.”

Of course, in order to do this well, Hoban warns, one must have an intimate knowledge with all meta relevant trends and standard decklists. Taking this into account, in conjunction with your opponent’s presumed skill level, can give you the appearance of mind reading if done well. If an average player is using a standard decklist and telegraphing obvious plays, then your guesswork is over. You already know what they will do and what you must do in response.

“We also can employ various tactics to get information out of our opponents. Most people aren’t very good at hiding information. Most people don’t even try to hide anything beyond the basic level of not playing with their hand revealed. This leaves them open for exploitation.”

The path to victory is to gain every possible advantage. Over the course of a long tournament, these little accruals of probability will add up and separate the top players from those that bubble out. Any small increase in victory which is left on the table is a waste and a tragedy. In that spirit, here are some of Hoban’s recommendations to milk valuable information out of your unsuspecting opponent:

Ask them about their record. People are all too happy to reveal their win/loss ratio as well as what beat them. Knowledge of what they lost to can help you to guess what deck they’re using before they play a single card.

Create a mutual enemy. If they express disdain for a particular card used in one of the top decks, then you can guess they aren’t personally using that deck. This has the added benefit of building rapport and good will that can be spent later for an advantage.

Phish some more with the help of foreign cards. It’s within the bounds of the rules to use foreign language cards so long as you can provide an English version of the card should one be requested. Under normal circumstances, players will ask to look at your card, read it, and hand it back to you. However, a foreign card does not grant them this luxury. They now must ask to see your English copy. This provides an opportunity for exploitation. You can helpfully volunteer to answer any question they might have in lieu of wasting the time hunting for your English copy. They might seem petulant if they turn down this friendly favor and outright ask for a particular piece of information, giving you added knowledge of what they’re considering.

“If they ask us a specific question about it, then we can infer from that the cards that they might have. We can learn to hear things like, “I was wondering if it could be targeted” as “I have a card that targets.” That is free information we wouldn’t have been able to get if they had just picked up the card and read it!”

Abuse the helpful nature of your fellow man.

“He found a way to be able to figure out who was playing Cairngorgon and who wasn’t. Justin realized that we could pick up our own Extra Deck and stare at a card for a few seconds, and then ask the opponent, “Do you have an English Cairngorgon I could read?””

Hoban’s circle knew that most opponent’s first reaction to a friendly request would be an obliging hand. So why not abuse this fact? His team needed to know if their opponents were using a particular card in order to evaluate the relative safety of an otherwise strong play. This knowledge would turn a coin flip into an assured victory. Throughout the entire tournament in which they performed this ploy, all players helpfully obliged them, many sealing their own doom in the process. The only one who managed to avoid doing so flat out forgot they were using the card and instead checked their trade binder rather than the cards they were using to play. Hoban’s team meanwhile leaked no useful information with this play, as they were not even using the card to begin with.

Phish, phish, phish! Make bold assertions about what your opponent is planning. Their responses will often reveal whether or not you were right. Puzzled looks, confused wonderment, and forced blankness all yield their own information theoretic advantage if only you can separate the signal from the noise.

IX. The Art of Persuasion or How I Learned to Stop Caring and Love the Dark Arts

“It’s an important distinction to make, as there is no such thing as “somewhat illegal.” It’s either illegal and not allowed or legal and allowed, and we need to make sure we are staying on the right side of the line.”

This section of the book is about particular ways to lead your opponent to the conclusions you want them to have. This goes beyond baiting them into believing you have a particular card or misdirecting them away from a winning play. It’s here that Hoban advocates convincing your opponent to make decisions against their own interests beyond the confines of the game itself.

His primary example is to convince your opponent to consent to a “gentlemen’s agreement” which benefits yourself but not them under the guise of fairness. In Yu-Gi-Oh!, as with many games, tournament matches are best-of-three with the ability to swap cards between your Main Deck and Side Deck between games. Hoban advocates spending some of your built-up rapport to declare a particular powerful card a common enemy between yourself and your opponent. By making that card out as an unfair element, you then suggest each of you remove your copy of the card in subsequent games for the sake of fairness.

Importantly, he only says to do this with an opponent who is worse than you. You want all the unfairness you can get your hands on to defeat a stronger opponent, but it would be an unneeded risk to allow a weaker opponent to get lucky and defeat you with a lucky draw.

“At the end of 2013, we kept losing to our opponents flipping Return from the Different Dimension. It seemed like we could win any game that they didn’t have it, but it being there was costing us a significant number of games. That’s when I came up with the idea of asking the opponent if we could both agree to side out Return from the Different Dimension. We could present Return as a mutual enemy and note that we should agree to take it out in the spirit of a ‘fair game.’

In reality, it had nothing to do with wanting a fair game. We were asking our opponents to side it out because we thought we were better players and that it being there benefited them more than it benefited us, as we felt we were more likely to win if neither player drew it. Being able to present the suggestion as being in the spirit of “fairness” got people to agree to it. It rapidly caught on, and has been replicated in many formats since.

Return was an unfair card. It was just more unfair to the better player. The beauty of offering the agreement only against players we thought were worse is that they weren’t good enough to realize that it benefited the better player more. They tied their own nooses.”

There are a number of other stories peppered throughout this section such as a player leaking false information about what they were using on social media mid-tournament to mislead those following them.

Perhaps the most infamous example of this tactic is to offer to mutually remove the single copy of an unfair card only to then re-add a second copy. Under normal circumstances, these blow-out cards are limited to one copy per deck and you simple reveal the single one you are removing. However, there was a rare occasion where the powerful card was allowed at three copies, but only used at one.

“Up until the Nekroz format, every card we had ever agreed to side out had been played at the maximum amount possible. Djinn was unique in that its searchability meant that playing more than one of it was unnecessary. For ARG Circuit Series Fort Lauderdale, I had the idea of side decking a second copy of Djinn, Releaser of Rituals. That way, we could ask to side a Djinn out, show them the one we were taking out, and then side in a second copy.

The idea got lots of attention, mostly negative, in spite of it being completely legal. I’m not one who believes in adhering to made-up rules that don’t exist outside of players’ minds.

Thinking that the Djinn move was unfair simply goes against the entire idea of asking to side out cards, as it was created to give the better player an advantage. Something is either legal and should be allowed or illegal and shouldn’t be allowed.

What I never told people was that I never actually sided in the second Djinn. I just took the heat for it so Ben didn’t have to, not that it matters. It was my idea, and I fully intended to execute it, but I just didn’t have a good chance to.

Would I consider doing it again? The only reason against it would be that doing so might cost me more future games. News of my tactic would spread, and people would refuse to take out some future card that they would otherwise agree to take out if I do not employ the strategy.”

Remember, this is the art of winning– and that translates into taking every little edge and advantage you can. Anything short of that would be to not take the endeavor seriously. Made up notions like honor and sportsmanship only serve to hold you back and artificially handicap yourself.

X. The Rest of The Book

What remains is an extremely in-depth systematized look at how to build a consistent, powerful deck. This section is extremely informative and a great resource for anyone building a deck for the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card game circa 2016.

Although all of Hoban’s advice about probability, variance, and comparative advantage remains true to this day, advice such as ratios of types of cards likely has to be adapted for the modern era of speed and power. His explanations about how to evaluate cards and solve problems during the deck building process are phenomenal resources. I’ve often said that deckbuilding is a skill not many players possess and even fewer seek to improve. Hoban is not one of those players.

He goes on to describe metagames at large, how to evaluate them, and how to gear your deck choices to suit them. Lessons to be learned here are very specific to constructed play of luck-based hidden information games, but are an interesting read for anyone interested in the deep well of meta-level skills employed in high level play.

XI. My Takeaways

During my reading of Road of The King I was constantly torn. Doing what Hoban recommends will absolutely make you more likely to win tournaments, but he never brings up what you would be trading off by doing so.

Patrick Hoban is a phenomenal player with the record to back up his boasts. Whenever he advocates for something questionable, I can only throw up my hands and shout, “But he’s not wrong!” All of his tactics will in fact increase your likelihood of winning tournaments, and that was the only thing he ever promised. To those that still protest, he never actually advocates cheating. Anything he does that’s questionable is within the bounds of the rules at the time the book was written.2 My other constant refrain was a sad “but the commons!” Hoban does actually bring up the tragedy of the commons, but only to advocate the rationally selfish choice.

“Thus, it makes sense to go ahead and introduce the degenerate strategy into the format and take the benefit before someone else can.”

And who can blame him?

What he writes is factually correct and will make you more likely to win. He never brings up what you’re trading off by doing so: honor, reputation, goodwill, and the ability to see your opponent as someone you can trust. He is not seeing those as trade offs in the first place. I expect he would be perfectly fine with any opponent using these tactics on himself and would say my rosy view of friendly opponents is an illusion that’s never been true of the game. To that I would say perhaps, but also perhaps not. It doesn’t matter anymore because the commons have been burned. For those familiar with the characters of the Yu-Gi-Oh manga, it’s Yugi Mindset vs Kaiba Mindset; opponents as playmates vs stepping stones on the path to victory.

I want to win without compromising my values or making the game less pleasant for everyone. But what constitutes good sportsmanship and how do we settle disagreements about it? Where does a bluff end and an outright lie begin? Some of the stories and tactics put forth by the book caused me to cheer in shared triumph at a spectacular play and show of mental skill.3 Others caused me to literally curse the heavens in indignation.

XII. Conclusion

Who should read this book?

Road of The King is one of the most novel books I’ve read in a long time. An unapologetically candid walk through the mind of one of a game’s best players. It pulls no punches. It leaves no stone unturned.

You, the reader, will absolutely walk away having learned something. But therein lies the rub. What will you walk away with? Those steeped in the traditions of the Rationality community will not learn anything new about epistemology. Hardcore competitive players of the Yu-Gi-Oh! Trading Card Game will not learn very much new about deck building theory, play fundamentals or metagame evaluation. Most of Hoban’s object-level advice has thoroughly proliferated through the competitive community. Those seeking out the dark arts would be better served by reading books more specifically tied to manipulation, gaslighting or mentalism.

There’s value in reading Road of the King as a handbook for winning tournaments, but it’s just as interesting to see it as a window into the soul of a pure Spike, unadulterated by any Timmy or Johnny tendencies. Patrick Hoban’s philosophy about hard work and the pursuit of victory is the true draw of this book.

So who is this for? Road of The King is for the narrow sliver of people who wish Seto Kaiba wrote The Sequences. If you’re one of the eight people on Earth that describes, then check it out.4

Note that this chart is a bit nonsensical. The "number of players" axis is in terms of percentages rather than numbers, it attempts to display skill as a continuous scale yet groups it into discrete categories, etc.

The March 2023 update to the Infractions and Penalties Policy of the game made many of the tactics espoused in the book explicitly illegal. Misrepresenting the gamestate, any claim of information that should be hidden, illicit agreements between players, and much more have been deemed unsportsmanlike behavior and subject to penalties up to and including disqualification.

Stories that made me cheer were not featured in this review due to relying heavily on knowledge of specific card effects to appreciate or understand.

If you’re interested in reading Road of The King, but don’t want to monetarily reward the behavior outlined in the book, you can always purchase a used copy like I did.